Of the questions I have been asked most often during my career as a minister, near if not at the top of the list, is some form of the question, “Where is God?” Or, when they are being more honest, they ask, “Does God really exist?” The evidence to the contrary often seems persuasive. War, crime, cancer, political events, natural disasters and now this seemingly unstoppable pandemic. Just last week in a Zoom call with friends I was asked this very question. How do we make sense of God when the world is coming apart at the seams? And then on NPR this past Tuesday I heard a guest on Fresh Air discuss this question with Terry Gross. Her guest, Jim McCloskey, is the founder of Centurion Ministries, an organization devoted to freeing people who have been wrongly committed of serious crimes. John Grisham calls him the “dean” of innocence projects. Inspired by an encounter with a convict on death row while serving as a prison chaplain, McCloskey succeeded in proving the man’s innocence and his work has now freed 63 men and women who were wrongly convicted.

McCloskey does not consider himself to be very spiritual. He struggles with prayer and many of the core Christian beliefs. During one difficult period, after witnessing police and other authorities blatantly lie about a man he knew to be innocent, he checked himself into a Catholic retreat center as an alcoholic might check into a sobriety program. He was having serious doubts about God and whether God existed, and if God did, whether the Divine cared about what was happening on earth. Does God ever intervene in human affairs? Does God even try to bring about justice for people who have been unfairly victimized by the State? Pray as he might, the answers did not come. He turned to the one spiritual practice that had helped him in the past, scripture. Turning to the Sermon on Mount in the 5th chapter of Matthew, he read, God “makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.” McCloskey told Gross that he came to understand that is just the way the world is and it gave him a different sense of the presence of God that is with us through good and evil.

Here’s the thing about that passage in the Sermon on the Mount. Immediately prior is the very familiar text in which Jesus says, “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven;” and then Jesus provides that statement which helped guide McCloskey out of his theological conundrum. Jesus continues to speak about love, adding, “For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same?” The impartiality of sun and rain are bookmarked by human love. In other words, if you are looking for God’s intervention in the world, do not look to forces of nature, look for actions of love. I don’t think it gets any clearer than this.

There are of course many reasons for why people may doubt God’s existence. It is not my purpose to engage in that debate or to establish any kind of proof for an ontological reality that is beyond physical evidence. Rather I simply want to challenge the assumptions that most often lie behind the existence question, namely, our understanding of the powers of that which we call “God.”

The chief quality most often given to God is omnipotence, the idea that God is “all-powerful.” Christian hymns often sing of the “Almighty God.” A popular hymn of the 18th century still sung today in many churches proclaims “Come, Thou Almighty King, help us thy name to sing.” Please note, my American friends, that monarchial metaphors for God come from a system that our country rebelled against. That alone should cause Christians today to rethink such imagery. If we would not tolerate an almighty king ruling over us on earth now, why do we praise one as our image for God ever? It isn’t just the “king” I find so problematic, but especially the “almighty”. For once we give that attribute to God, the problem of evil becomes hugely difficult to solve. If God is all-powerful, why does God not do something about all the evil in the world? Surely an Almighty God could stop this pandemic, if God so desired. So then the question becomes, why doesn’t God do that?

The Hebrew people dealt with this question in a major way during the Babylonian captivity after the destruction of Jerusalem in the 6th century BCE. One answer was developed by what biblical scholars call the “Deuteronomist,” the name given to what was most likely a collection of editors who put together much of what we now know as the Old Testament. The “Deuteronomic history” tells the story of the Hebrew people from the call of Abraham and Sarah to the fall of Jerusalem. In their view, that fall and the destruction of God’s temple could only mean that it was God’s will. Bad things don’t happen to good people unless God wills it. The conclusion of the Deuteronomist, therefore, was that the fall of Jerusalem must have been punishment for the sins of the nation and especially those who ruled it.

What is always fascinating about scripture, however, is that there is never just one answer to such big theological questions. The author of Job was not comfortable with the Deuteronomist’s solution. Job, you may recall, is innocent and does not deserve his suffering. Job’s so called “friends” try to convince him that he must have done something to deserve this treatment from God and therefore he must repent. Like the innocent man McCloskey met on death row, Job insists on the justice of his cause and dares to demand to hold God to account. After 37 chapters struggling with these weighty issues, God finally appears and reveals that Job is indeed a righteous man, but not so righteous that he can question the motives of God. Job’s fortunes are restored (though the lives of his lost loved ones are not) and lives happily thereafter. The solution the story of Job provides is not very satisfying, but the power of Job is in the questions it asks which unmask the over-simplistic answers given by the Deuteronomist. Bad things do happen to good people and so long as you hang on to the omnipotence of God you will never find a satisfying answer as to why.

Rabbi Harold Kushner answered this ancient dilemma in his bestseller on the topic which was published while I was in seminary and much to the excitement of my professors. By the time they got him to campus, “When Bad Things Happen to Good People” had already sold millions of copies. The stories I heard Rabbi Kushner tell in the packed auditorium that day still resonate within me. He told of speaking to a large audience in Europe where he was asked about the implications of his theology for nuclear war. Would God intervene to stop us from destroying the earth? Kushner paused for a moment and told his audience that he had never been asked that before and hadn’t given it much thought, but he said, he would have to conclude no, God would not intervene because God could not intervene and if that meant God had to start over again with nothing but insects, God would. Whereupon his host, the bishop of the church in that country, stood up to say, with all due respect to their guest, he could not believe God would allow such to happen.

Here is why Kushner holds to such a view. One of two things can be true: either God is all-powerful or God is all-loving, but God cannot be both. If you see your child playing in the street as a fast moving truck approaches, what loving parent would not move quickly to save their child? Indeed, what kind of any person would not do so for any child? All those theories about “free will” and that God allows us the freedom to fail simply break down when you consider the evidence of history. The Holocaust should have been all the evidence we needed to show that either God does not care about humanity or God does not have the kind of power we often think God has. Given the choice, Kushner chooses to believe in a God who is all-loving rather than a God who is all-powerful. So do I.

The reason Kushner was brought to my seminary, the School of Theology at Claremont (STC), was not just because he was a popular author. STC was the center for what is known as “process theology,” a way of thinking about God and reality developed by Alfred North Whitehead who was a mathematician and a contemporary of Albert Einstein. Like Einstein, Whitehead sought to develop a unifying theory for all that is known in a philosophy taught today as “process thought.” In a nutshell, process simply says that the ultimate reality consists not of material things but of events. The basic mechanics of the universe are better understood not by the study of material things, but by the study of relationships and how everything interacts with one another. In developing his theory, Whitehead, the son of a minister, could only explain novelty by the existence of God. Otherwise all events would simply be the sum of their past. There is, Whitehead believed, a “lure” which constantly calls us to a higher order and greater good. That “lure” comes from God’s will, which we experience as the will to love. Kushner, without knowing it, was expressing the basic concepts of process theology when he wrote his book.

Critics of this view who cannot give up on the idea of God’s omnipotence point to the stories of scripture from creation to the resurrection of Jesus. If God is not omnipotent, they argue, everything else in scripture collapses. But as the example of Job demonstrates, scripture does not provide a unified theory of God and God’s power. Take the creation account for instance. Genesis records not one but two different creation stories with a different order and purpose (compare Genesis 1:1-2:4a to 2:4b-25). The emphasis in the first account is on the goodness of creation, culminating not in the creation of humanity–as John Dominic Crossan notes, we are created on a later Friday afternoon and nobody does their best work on a late Friday afternoon!–but it culminates in the day of rest. Creation culminates in sabbath—there is a viewpoint we need to take more seriously!

The second creation story begins with the creation of the first human being and the creation of the Garden of Eden with it’s tree of knowledge of good and evil at the center. The emphasis in that story is on the perversion of that knowledge and the destruction that results, leading to the loss of Eden and the first murder. Now there is a sermon that will preach today!

There is much more packed into these two stories at the beginning of scripture. By placing them side by side the editor or editors who assembled the book of Genesis (the Deuteronomist?) reveal a critical aspect of scripture that most Christians today have not taken seriously enough. First, that many of the stories of scripture are much better understood as metaphor and parable, not as literal history or scientific fact. Second, when you have that understanding, the power of God is not best expressed in the movement of atoms and physical things, but in relationship.

Take but one example, the story of Jesus walking on water. Is the point of that story that Jesus has such miraculous power over physical matter? Or is the point about trusting one’s relationship with God to “step out of the boat”? If the former, then God can change the direction of hurricanes and when God doesn’t, then it must be because God wills that destruction upon those victims. And so the not so reverent John Hagee famously blamed homosexuals in New Orleans for the destruction of hurricane Katrina. In reality Hagee was blaming God for that death and destruction. If I held such belief, I would renounce Christian faith. The damage Hagee caused with his comments were arguably greater than those caused by the hurricane. Hagee’s poor example of Christian faith may be the extreme, but it illustrates the theological dilemmas we create by holding onto the notion of God’s omnipotence.

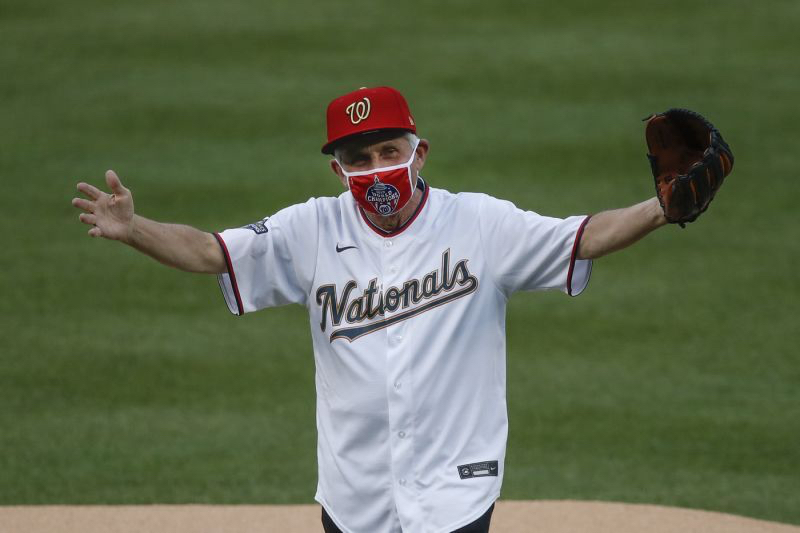

If God cannot stop this pandemic, what is God doing? So here’s my image for God: Dr. Anthony Fauci throwing the opening pitch for the 2020 baseball season. If you have been following the news, you may think I’ve lost my marbles! The good doctor’s pitch was widely off the mark–charitably described by one observer as “socially distant”! How can such be an image of God? Because the power of God is not about throwing a perfect strike. It is about everything else that Fauci represents—speaking truth to power, working to persuade (“lure”) a reluctant people and government to do the right thing, working for the health of people, respecting the knowledge of science, and somehow in it all, keeping a spirit of gentleness and humility. God bless Dr. Fauci!

So if you are looking for God in this pandemic, look for signs of love, not the power of a 98 mph fast ball, and there you will find God.

Dan, thanks so much for this excellent piece. You were introduced to me by our common friend David Wagner. As a proud CST grad (‘79) I really appreciate this introduction and will enjoy following your blog!

Nice to hear from you Mark!

Good stuff. I barely understood process theology when I was at Claremont, but in the dimness of my faulty memory, it hinted at what I sensed was a way of sensing the Holy. Thank you so much for writing this. I shoved it onto my Facebook page. I was lured to do so . . .

Oops, put my reply in the wrong box so adding this just to make sure you see it!

Thanks Larry. I was totally captivated by John Cobb and David Griffin and have been a devotee ever since. When I was in Fresno I went back every year for the “Process and Faith” group that worked on process materials to use in churches. Sorry I had to give that up when I moved to Oregon, but have tried to stay in touch. It is indeed an irresistible lure!

Perhaps your “Process and Faith” group will be revived in Salem!

Interesting idea. Is the Cobb chair at CST or the Center for Process Studies moving with the school? Guess I should look into that.

Your blogs are always mentally stimulating. More! More!

Thank you, Dan. We need your voice of wisdom during this troubling time.