Most citizens of this country could probably cite a phrase or two from the first two amendments to the Constitution (e.g “freedom of speech” or “the right to bear arms” to name one from each), but beyond that, not so much. Most would recognize the famous phrase from the Fourteenth Amendment even if they couldn’t tell you a wit about it’s origin. “Equal protection of the law”, the fundamental principle of the 14th Amendment and American jurisprudence ever since, is the basis of any number of rights we now take for granted. (Actually it is “laws” (plural) in the amendment but oddly the singular sounds more encompassing and so we say things like, “Everyone is treated equally under the law.” Well, at least in theory. Read on.)

Even more likely people will know the doctrine created by the Supreme Court when interpreting the 14th Amendment in the now infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case decided in 1896. Sixty-two years before Rosa Parks made her fateful ride on that Montgomery bus, Homer Plessy boarded a train in New Orleans heading north. Seven-eights Caucasian and one-eight Black, Plessy was told by the conductor that he would have to sit in the car for “colored races.” Plessy refused and was arrested for breaking a Louisiana law passed in 1890 that required segregation in public transit with “equal” accommodations. The judge presiding in the trial that convicted Plessy was John Ferguson, who Plessy then sued, claiming that the equal protection clause of that the 14th Amendment made the Louisiana law unconstitutional.

Writing for the majority with only a single dissenting vote when the case made it to the Supreme Court, Justice Henry Brown opined that the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868 as part of Reconstruction after the Civil War, only applied to civil and political rights, like voting, and not to social rights, like choosing where to sit on a train. Hence, the “separate but equal” doctrine was born which would be the basis for all Jim Crow laws thereafter. For nearly 60 years it remained the law of the land until Chief Justice Earl Warren declared in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that “separate but equal” was anything but and that segregation had no place in public schools. Reversing Plessy v. Ferguson, Justice Warren declared that the plaintiffs in the Brown case were “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.” Note the odd twist of history, two Browns, one White and one Black—the Hon. Henry Brown, Justice of the Supreme Court, received the judicial equivalent of a knock out by nine year-old Linda Brown, denied entry into the all-white school whose existence was based on Justice Brown’s earlier decision. That is equal protection of the law. The year after Brown v. Board of Education, Rosa Parks took the seat denied to Homer Plessy and, as they say, the rest is history.

Flash forward 76 years and the 14th Amendment once again is about to take center stage in another moment of national crisis, the pandemic. How, you might wonder, could an amendment crafted to guarantee the rights of former slaves as citizens of this country have anything to do with a pandemic? Well, it turns out, we have been here before. The very same issues of personal freedom and public health that are being debated today around vaccine mandates have already been debated before the Supreme Court. Then it was smallpox, a disease so deadly that it killed nearly a third of those who had it. Fortunately the vaccine for smallpox is as old as this country. The precedent for President Biden’s recent Executive Order was set by no less than George Washington who had his troops vaccinated for smallpox.

The vaccine wasn’t perfect. A young man in Sweden developed a painful rash from the vaccine that took years to heal. His name was Henning Jacobson. He emigrated to the U.S. and became a Lutheran minister in Cambridge. In 1904 those charged with protecting the public health of Cambridge ordered all adults to be vaccinated against the dread disease or be fined $5. Rev. Jacobson, citing his bad experience and the guarantee of certain personal freedoms under the Constitution, refused to be vaccinated once again. In an argument that would sound very familiar to many today, Jacobson argued that the freedom to make certain medical choices about ones’s own body is one of the most basic freedoms. His right to liberty was being infringed without the due process of law as provided in the 14th Amendment. It is a reasonable position.

Writing for the majority in a 7 – 2 decision, Justice John Marshall Harlan ruled against Jacobson in 1905. “There is, of course, a sphere within which the individual may assert the supremacy of his own will and rightfully dispute the authority of any human government,” Harlan wrote. “But it is equally true that, in every well ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.” Harlan provided examples, such as requiring foreign travelers to quarantine against their wishes when entering the U.S. or conscription in times of war. The principle provided by the Court is straight forward, the interest of the public must outweigh that of the individual in certain times. “There are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good,” said the Court. “On any other basis, organized society could not exist with safety to its members. Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy.” (For more on Harlan and Jacobson, see Politico.)

Read that last sentence again. “Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy.” Your personal freedom is necessarily limited by the common good of others. Otherwise there would be no need for things like driver licenses and building codes. Just as free speech does not entitle you to yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater when there is none, so too personal liberty does not entitle you to put others at risk by smoking wherever you want. Same with vaccines, though incentives are always preferable to coercion. If you have no medical reason to refuse it, is it reasonable for society to place sensible limits on your freedoms, like requiring you to be tested or limiting the jobs you can do, in the interest of protecting the health of all? I admit a certain doubt, but in the end concur with Justice Harlan who understood well that the scales of justice and equality of the laws only work when the common good and personal freedom are in proper balance.

Will the current court follow the precedent laid down so clearly in 1905? It is likely only a matter of time before we will find out and the President’s Executive Order is challenged in court. The nine Supremes might want to take another look at Plessy v. Ferguson while they review their history, but at the minority opinion, not the majority. That single voice of dissent written back in 1896 with Jim Crow in its infancy, said this: “I am of the opinion that the statute of Louisiana is inconsistent with the personal liberties of citizens, white and black, in that State, and hostile to both the spirit and the letter of the Constitution of the United States. If laws of like character should be enacted in the several States of the Union, the effect would be in the highest degree mischievous.” That, in a nutshell, is the story of Jim Crow, mischievous writ large under the watchful eye of the likes of Robert E. Lee up to this very past week. Had the other eight listened to their dissenting colleague back then, “separate but equal” would have died in infancy and the legacy of Plessy might be a badge of honor instead of one of shame for SCOTUS. And they just might listen because his portrait hangs in the room where they make their deliberations. His name is Justice John Marshall Harlan, the voice of dissent on Plessy and the voice for public health on Jacobson. May both opinions hold true now and forever.

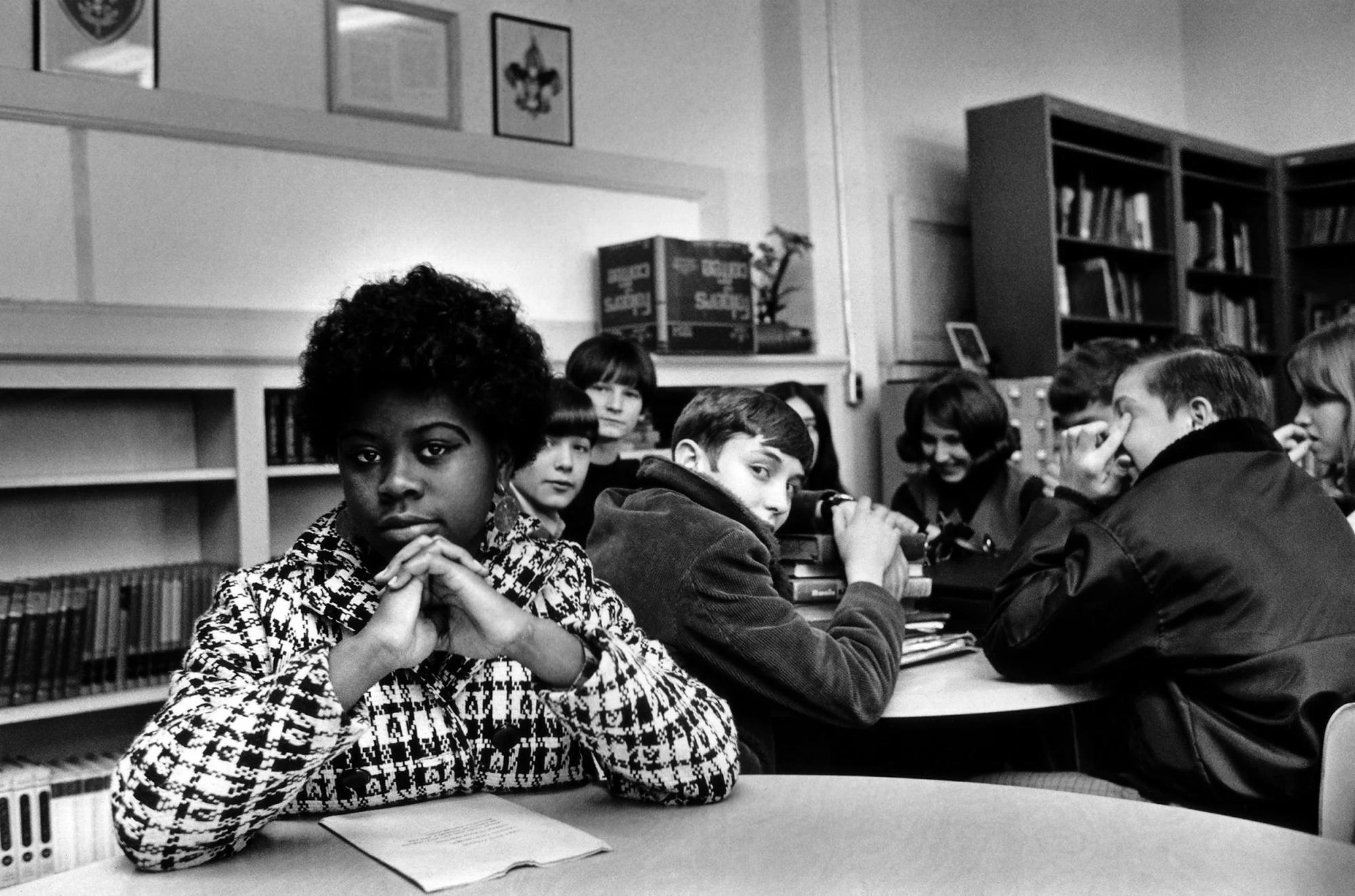

Photo: Linda Brown, one of the plaintiffs in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, in an undated photo from the AP. Ms. Brown died in Topeka in 2018 at the age if 76. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/linda-brown-student-1954-ruling-ending-school-segregation-dies-n860226